This post is part one in a three part series on the challenges of improving a production machine learning system. Find part two here and part three here.

Suppose you have been hired to apply state of the art machine learning technology to improve the Foo vs Bar classifier at FooBar International. Foo vs Bar classification is a critical business need for FooBar International, and the company has been using a simple system based on a decade-old machine learning technology to solve this problem for the last several years.

As a machine learning expert, you are shocked that FooBar International hasn’t gotten around to modernizing this system, and you are confident that replacing the Foo vs Bar classifier with the latest machine learning hotness will dramatically improve system performance. You pull the Foo vs Bar training data into a notebook, spend a few weeks experimenting with features and model architectures, and soon see a small increase in performance on the holdout set.

Next, you work with the engineering team to run an A/B test comparing your new model to the existing system. To your surprise, your new model substantially underperforms compared to the existing system.

This is a familiar story that anybody who has built machine learning models at a large company will recognize. Making measurable improvements to a mature machine learning system is extremely difficult. In this post, we will explore why.

Broken Abstractions and Unstable Systems

Machine learning systems are extremely complex, and have a frustrating ability to erode abstractions between software components. This presents a wide array of challenges to the kind of iterative development that is essential for ML success.

Justifying Infrastructure Investments

Most software systems carefully control which layers need to communicate with each other and which data needs to be exposed along each layer boundary. It is quite common for a new machine learning system to require breaking existing abstractions and connecting layers that were designed as separate.

For example:

- A new feature normalization strategy may require exposing raw data to a part of the system that was designed to consume processed data.

- Migrating a feedforward neural network to a graph neural network may require accessing the features of a node’s neighbors at inference time.

- Adapting a model to consume the predictions of another model as features may require configuring the models to run in sequence rather than in parallel.

Modifying software architecture and abstractions to support new products is common and healthy. However, it is difficult to execute these kinds of changes effectively before we have a clear understanding of what the next stable state of our software architecture should be. Unfortunately, this is exactly the case with machine learning improvements. Until we can test the machine learning system in production, we cannot determine how much value it will bring. This kind of catch-22 can dramatically slow down development and experimentation agility. In larger organizations where such a refactor may require multiple teams to prioritize the changes, this can lead to a state of paralysis.

In some situations it may be possible to build a modified version of the new machine learning system that operates within the constraints of the current software abstractions. For example, perhaps the fancy new model can execute in a batch job rather than in realtime. However, it is usually difficult to estimate how much this kind of modified design will handicap model performance. It is quite common for a state-of-the-art machine learning system that is deployed under such a handicap to underperform a simpler system that has been optimized for the abstractions of the software system it lives within.

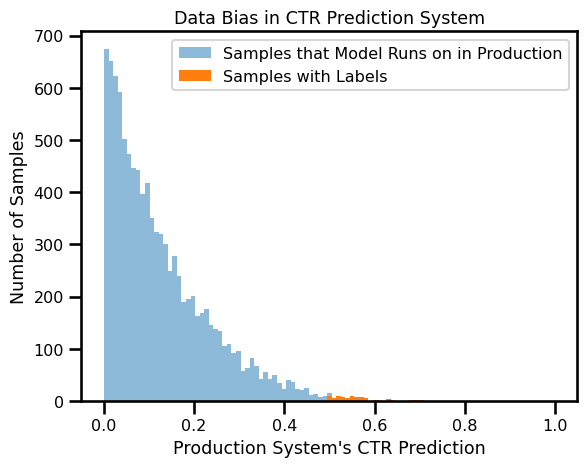

Distribution Mismatch

It is very rare that the distribution of samples for which we have labels is the same as the distribution of samples for which we have to perform inference. For example:

- Click-through-rate (CTR) prediction models do not receive labels on samples that the user did not see.

- Most content moderation systems receive feedback on only a tiny, typically non-representative subset of data.

- Most sensor analytics algorithms are built on top of labeled datasets that have unrealistically low noise levels.

In any of these scenarios, our model’s performance on labeled data presents only a skewed view of how the model performs on all traffic. There are some techniques like importance sampling that can minimize the impact of this bias, but these strategies can be quite hard to tune.

To make matters worse, it is quite common for data distributions to shift over time. In some circumstances these shifts can happen quite rapidly: it is not uncommon for models at large social networking companies to go stale within hours (example).

The combination of these effects can make it extremely difficult to draw conclusions about model performance improvements from offline results. In practice online A/B testing is usually required to draw more reliable conclusions by tracking metrics like revenue and report rate over all traffic. However, this substantially increases the iteration time required to make model improvements, which slows down progress.

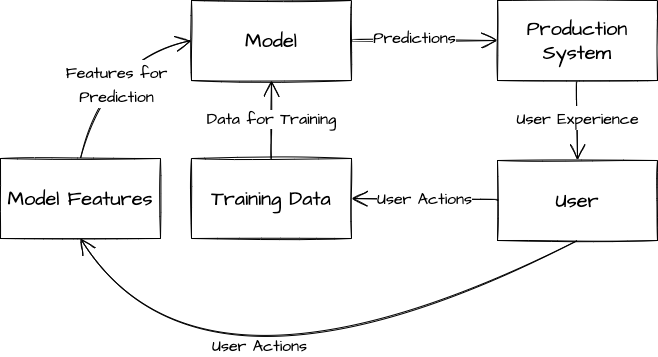

Feedback Loops

In many circumstances the labeled data that our model receives is dependent on the predictions it generates. Some classic examples of this situation include:

- Most recommender systems don’t receive user feedback on any sample that the user did not see.

- Systems that effectively detect and penalize users for certain behaviors may cause users to modify their behavior to avoid penalty.

- If a content moderation system is trained on user reports, then increases in system coverage may elicit decreases in model training data as user report rates decrease.

Furthermore, labeled data is not the only kind of feedback loop that can plague machine learning systems. It is also quite common for the features that a machine learning system consumes to depend on its predictions. For example, a common feature in recommendation systems is the number of previous times that a user has seen content of type X. This count will be heavily influenced by how biased the recommendation system is towards recommending content of type X.

This is a particularly insidious kind of distribution mismatch, since it can give rise to extremely complicated system dynamics.

We can sometimes minimize the impact of feedback loops by deriving training data from specialized pipelines that do not use the machine learning model directly. However, this strategy can be difficult to scale, can sometimes hurt model performance by preventing the model from learning from its mistakes, and does not directly address the influence of feedback loops on model features.

Unknown Tight Couplings

In production machine learning systems seemingly independent components often exhibit hidden tight couplings. This can make experimentation challenging. Changing one system without changing the other will cause performance to degrade, and changing both systems at the same time is often error prone and coordination intensive. Some examples include:

- Once a feature pipeline is developed and made available for model utilization, any change to that pipeline (even correcting errors!) risks damaging the performance of models that consume that feature. This forces ML engineers to version all feature changes, which causes feature pipelines to grow into unwieldy monsters extremely quickly.

- In large scale recommendation systems it is common for a light ML model or heuristic-based candidate generation system to select the set of candidates that a heavy machine learning model chooses between. Any change to the candidate generation system would affect the distribution of samples that are fed to the heavy model, which could affect that model’s performance.

- It is quite common for some models, such as semantic models or object detection models, to produce signals that other models consume as features. In this situation any change or improvement to the upstream models could damage the performance of the downstream models that consume their predictions.

When designing or working with an ML system, it is extremely important to be aware of the tight couplings that exist. In certain situations it can be beneficial to introduce redundant components in a system in order to relax the number of components that are tightly coupled.

To Be Continued

That’s all for now. In our next post we will explore some of the challenges of adding new features or improving existing features in a machine learning system.