Let’s talk about making assumptions. Each time you form an opinion on something, you don’t re-examine each of the beliefs that contributed to that opinion. For example, when you order food at a restaurant, you pick the foods that you think will taste good. You don’t spend hours questioning the structure of your palate or why you find hunger unpleasant. Generally, this works well for us. The unconscious assumptions we make stand, and our final decision is a good one. However, when our assumptions fail we can find ourselves in situations where we are highly confident in our decision, yet completely wrong.

There are a number of popular mathy brainteasers that illustrate how easy it is to get led astray by assumptions. I’m going to talk about 2 of them today: The Monty Hall Problem and The Blue Eyed Islanders Problem.

The Monty Hall Problem

The Problem (wikipedia version)

Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, “Do you want to pick door No. 2?” Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?

The Wrong Solution

At the beginning, there is a 1/3 chance of the car being behind any door. The host didn’t move anything, so obviously there is still a 1/3 chance and there isn’t any point in switching!

The Actual Solution

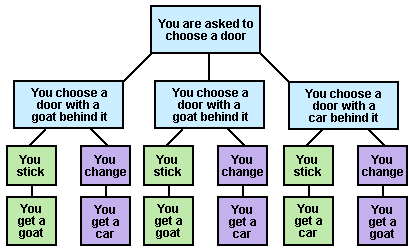

- Say you choose to not switch. Then if you initially picked one of the doors with a goat, you will receive a goat, and if you initially picked the door with a car, you will receive a car. Since there is a 1/3 chance that the door you initially picked has the car, you have a 1/3 chance of winning the car.

- Say you choose to switch. Then if you initially picked one of the doors with a goat, you will receive a car, and if you initially picked the door with a car, you will receive a goat. Since there is a 2/3 chance that the door you initially picked has a goat, you have a 2/3 chance of winning the car.

Therefore, it is in your interest to switch.

Why it’s Hard

When faced with the Monty Hall problem, people tend to make the assumption that since the goats and the car weren’t moved, the probability of success of each door doesn’t change throughout the course of the problem. However, this is a faulty assumption. The probability of an event depends on information. Consider the following scenario:

You pick a card from a deck at random and place it face down without looking at it. With no additional information, there is a 1/52 chance that card is the Ace of Spades. Now let’s say that you turn the card face up, and you see that it is indeed the Ace of Spades. The probability that card is the Ace of Spades is now 1, even though you haven’t changed anything about the card.

If that seems too obvious to you, consider another scenario:

You are playing cards with a dealer, and he places all of the cards in front of you. He tells you that if you can pick the Ace of Spades, he will give you a prize. You pick a card at random and place it face down without looking at it. Next, the dealer turns 50 of the remaining 51 cards up, demonstrating to you that none of them are the ace of spades. He asks you if you would like to switch with the remaining face down card. Clearly, it is in your interest to do so.

When the host displays a door to you, he is giving you information about the closed door - that either you picked a goat and that door contains the car, or you picked the car and that door contains a goat. This information changes the probability of the car being behind that door.

The Blue Eyed Islanders Problem

The Problem (Randall Munroe version)

A group of people with assorted eye colors live on an island. They are all perfect logicians – if a conclusion can be logically deduced, they will do it instantly. No one knows the color of their eyes. Every night at midnight, a ferry stops at the island. Any islanders who have figured out the color of their own eyes then leave the island, and the rest stay. Everyone can see everyone else at all times and keeps a count of the number of people they see with each eye color (excluding themselves), but they cannot otherwise communicate. Everyone on the island knows all the rules in this paragraph.

On this island there are 100 blue-eyed people, 100 brown-eyed people, and the Guru (she happens to have green eyes). So any given blue-eyed person can see 100 people with brown eyes and 99 people with blue eyes (and one with green), but that does not tell him his own eye color; as far as he knows the totals could be 101 brown and 99 blue. Or 100 brown, 99 blue, and he could have red eyes.

The Guru is allowed to speak once (let’s say at noon), on one day in all their endless years on the island. Standing before the islanders, she says the following:

“I can see someone who has blue eyes.”

Who leaves the island, and on what night?

The Wrong Solution

Everyone on the island hears the guru’s statement, and then thinks to themself “well duh, I see someone in this crowd with blue eyes too.” Since the guru’s announcement obviously didn’t tell anyone anything that they didn’t already know, nobody leaves the island.

The Actual Solution

Amazingly, the above solution is wrong. On day 100 all 100 blue eyed islanders will leave. Before we get into why this is the case, let’s note that the guru’s announcement DOES give every islander some additional information. Starting on the day of the guru’s announcement, up until the day that all of the blue eyed islanders leave, each islander learns that nobody could figure out the color of their own eyes in the past n days.

Here is the solution:

Let’s start by assuming that there is 1 blue eyed islander. He will leave on the day of the guru’s announcement, day 1. Now consider the case where there are 2 blue eyed islanders. Each of them sees only one other islander with blue eyes. Neither of them will leave on day 1, and when they see that the other blue eyed islander did not leave, they realize that they must have blue eyes as well. Therefore, they both leave on day 2.

Now let’s say that there are 3 islanders. Each of them sees 2 other islanders with blue eyes, and know that if there are 2 blue eyed islanders, they will both leave on day 2. When this doesn’t happen, each of them realizes that they must have blue eyes, and they all leave on day 3.

If we continue this logic all the way up to 100 islanders, we see that all 100 islanders will see that nobody leaves on day 99 and will leave on day 100. The formal inductive step is:

Assume that if there are n blue eyed islanders, they will all leave on day n. Consider the case where there are n+1 blue eyed islanders. On day n, each of the blue eyed islanders observes that no islander leaves. Therefore, they all realize that there must not be n blue eyed islanders, and that they must have blue eyes. Therefore, all n+1 islanders leave on day n+1.

People often have 2 questions about this solution:

- What quantifiable piece of knowledge does the guru provide?

- Why do the islanders need to wait until the 100th day to leave the island?

To quantify the information that the guru provides, we need to look closely at exactly what the islanders know before the guru speaks. Let’s think about the case where there are 2 blue eyed islanders. Both islanders already know that there is at least one blue eyed islander. But until the guru speaks, each of the blue eyed islanders may think that the other was not aware of the presence of a blue eyed islander.

When there are 3 blue eyed islanders, we get even more meta. Each of the blue eyed islanders knows that there is at least one blue eyed islander. And each of the blue eyed islanders knows that each of the other blue eyed islanders knows that there is at least one blue eyed islander. However, no blue eyed islander knows that each of the other blue eyed islanders know that each of the other blue eyed islanders know that there is at least one blue eyed islander. For example, blue eyed islander #1 does not know that #2 knows that #3 knows that there is at least one blue eyed islander.

At each recursive step where blue eyed islander n is reasoning about blue eyed islander n-1’s knowledge, islander n reasons that islander n-1 is not aware of his own blue eyes. Therefore, the number of blue eyed islanders effectively decreases at each level of meta-knowledge. When the guru speaks, each islander learns that each other islander knows that each other islander knows that each other islander knows that…(repeated n times)…there is at least one blue eyed islander.

So why don’t the blue eyed islanders leave immediately? Why wait for 100 days to pass? The answer is that no blue eyed islander has learned enough to infer his/her own eye color. All he/she’s learned about is the other blue eyed islanders’ knowledge. On each of the next 98 nights, each blue eyed islander will learn a little bit more about every other blue eyed islander’s knowledge, and on the 99th night the blue eyed islanders will be able to deduce their own eye colors.

To illustrate this, lets consider the case with 4 blue-eyed islanders. After the announcement, #1 learns that #2 knows that #3 knows that #4 knows that there is at least one blue eyed islander.

After the first night, when nobody leaves, #1 learns that #2 knows that #3 knows that there are at least 2 blue eyed islanders.

After the second night, when nobody leaves, #1 learns that #2 knows that there are at least 3 blue eyed islanders.

After the third night, when nobody leaves, #1 learns that there are at least 4 blue eyed islanders.

Therefore on day 4 every blue eyed islander leaves.

In the 100 person case, we can say that after seeing nobody leave the island on day n, #1 knows that #2 knows that…(repeated 100-n times)…#(100-n) knows that there are at least n+1 blue eyed islanders.

If you’re interested in further discussion about this solution, check out this thread.

Why it’s Hard

This problem is hard because of how obvious the guru’s statement seems. Most people would assume that a statement that by itself doesn’t contain any new information would be unhelpful. It’s incredibly hard to get past this mental block and think about how the knowledge and behavior of the other islanders in the context of the statement could provide information.

Part of this, I think, is because we can’t help but imagine ourself as a blue eyed islander listening to the guru’s announcement, looking at 99 other blue eyed islanders and thinking “well duh.” Try as we might, we are not perfect logicians, and it’s hard to think like one. It’s even harder to reason based on the assumption that other people will act like perfect logicians, given our extensive experience with people’s consistently irrational behavior.

Thank you to Paul Martin and Eric Sporkin for ideas and feedback.