One of my favorite classes in college was Abstract Algebra. It was my first non-CS non-elementary math class, and I took it because I knew I didn’t want to graduate without having broadened my mathematical horizons beyond CS.

As it turned out, Abstract Algebra felt pretty familiar. Many of the constructs we form and play with in Algebra underlie many CS fields, such as crytography and graph theory. There is also a lot of overlap between the tools used in Algebra and CS, such as homo/isomorphisms.

Mathematical Structures

Many mathematical fields share a common theme - define some structures (often types of sets) then prove things about them. In Computation Theory, the structures are automata and languages. In Calculus/Real Analysis, the structures are continuous, differentiable, riemann-integrable, etc real valued functions of real variables. In Abstract Algebra, the structures are groups, rings and fields.

There are some similarities between mathematical structures and the classes of object-oriented programming. Often we study general structures that must obey some axiom, and then define “subclasses” of those structures that obey additional axioms. For example, rings are subclasses of groups - they satisfy all of the same axioms, but they add an additional operation and some additional structure.

Why do we spend the effort developing and proving theorems about general mathematical structures? For the same reason that we define classes and subclasses rather than build each object seperately - to minimize redundancy and reduce complexity. When we’ve proven a theorem about a particular structure, then that theorem applies to everything with that structure. If we define a new structure as a special case of a parent structure, then all of the work that we’ve done to understand the parent structure applies to the child structure as well.

Consider writing a program in Java where you define a method that accepts a “foo.” Then you can write that function with the certainty that anything passed in will have access to all of foo’s methods. When we write a proof about groups it’s the same idea - regardless of the inner workings of the infinite different groups, we know that as long as we build the proof on the group axioms it will hold for all groups.

The Group

One basic structure in Abstract Algebra is the group. A group is a set, which we will denote by \(G\), combined with a “group operation,” which we will denote by \(*\), that satisfies the following axioms:

- For all \(a,b\) in \(G\), \(a*b\) is also an element in \(G\) (\(G\) is closed under \(*\))

- For all \(a,b,c\) in \(G\), \((a*b)*c = a*(b*c)\) (\(*\) is associative)

- There is an identity element \(1\) in \(G\) such that \(a*1 = 1*a = a\)

- For all \(a\) in \(G\), there is a \(b\) in \(G\) such that \(a*b = b*a = 1\) (every element in \(G\) has an inverse)

Note that this definition does not require that \(*\) be commutative, that is, for many groups \(a*b \neq b*a\). Groups where \(*\) is commutative are called “abelian” groups.

Examples of Groups

Groups are everywhere in mathematics, and you’ve probably worked with many groups in the past without realizing it.

Example 1: Integers and Addition

The integers (\(G\)) and the addition operation (lets use \(+\) rather than \(*\) for clarity) form a group. Let’s prove it.

- The sum of two integers is an integer, so \(G\) is closed under \(+\).

- Addition is associative

- For any integer, \(a\), \(a + 0 = 0 + a = a\), so \(0\) is the identity element.

- For any integer, \(a\), \(a + -a = 0\).

Note that the integers and the multiplication operation don’t form a group, since the multiplicative inverses of integers are usually not integers (they are rational numbers). However…

Example 2: Integers and Multiplication modulo \(P\)

If you haven’t encountered modular arithmetic before, there is a great introduction here. As a refresher, \(x\) \(mod\) \(n\) is the remainder of \(x/n\).

Some of the astute readers might now be asking “what about modular arithmetic? Do the integers and multiplication modulo \(n\) form a group?” This is a great question, and the answer is “sometimes.”

Let’s consider the integers \(1...n-1\) and the operation multiplication modulo \(n\). For two integers \(a, b\), \(a*b\) \(mod\) \(n\) must be less than \(n\). Since \(a*b\) \(mod\) \(n\) is only \(0\) when \(a*b\) is divisible by \(n\), then as long as \(n\) is prime, \(a*b\) \(mod\) \(n\) will be in \(1...n-1\).

That proves the closure condition (condition 1). For the other 3 conditions:

- Multiplication is associative

- For any integer, \(a\), \(a * 1 = 1 * a = a\), so \(1\) is the identity element.

- The proof of the existence of multiplicative inverses is a little complicated and relies on Bezel’s theorem, you can find it here.

Therefore the set of integers \(1...n-1\) and the multiplication modulo \(n\) operation form a group if \(n\) is prime.

Example 3: Rotations of a square (and cyclic groups)

Let’s step away from numbers for a moment. The “rotational symmetries” of a polygon are the different mappings of the polygon to itself by rotation. Consider some triangle \(ABC\). We can enumerate the rotational symmetries of \(ABC\) by sequentially rotating \(ABC\) by \(120\) degrees. Lets denote “no rotation” of \(ABC\) as \(r^0\) or \(1\), and \(n\) rotations of \(ABC\) as \(r^n\).

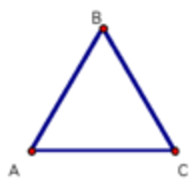

This is \(1\):

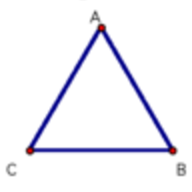

This is \(r\):

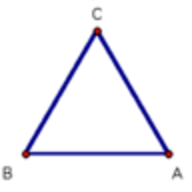

This is \(r^2\)

Note that \(r^3 = r\). Now, lets prove that the set of rotational symmetries of \(ABC\) along with the rotation operation forms a group.

- If we rotate \(ABC\) \(a\) times, and then rotate it \(b\) times, this is the same as rotating \(ABC\) \(a+b\) times, so \(r^a * r^b = r^{a+b}\), and the closure condition holds.

- Since the order of rotations doesn’t matter, the associativity condition holds.

- Since the “no rotation” element does not change the orientation of \(ABC\), then \(1\) is the identity element.

- Since we can always rotate any rotational symmetry of \(ABC\) back to the original orientation, (i.e. \(r*r^{2} = 1\) and \(r^{2}*r = 1\)), each element has an inverse.

Notice that the proof above applies to more than just \(ABC\) - it applies to any regular polygon.

Other Resources

If you’ve enjoyed learning about groups and you want to learn more about them and other algebraic structures, I recommend Dummit and Foote. This textbook is extremely readable and contains an extraordinary number of worked examples and well-fleshed-out proofs.