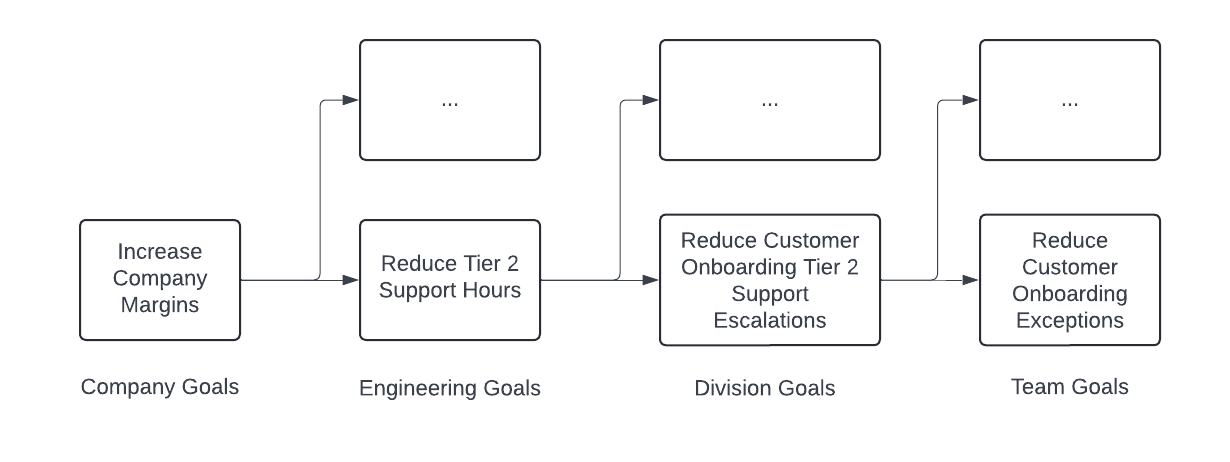

The CEO needs to increase company margins. He turns to the engineering leadership team to help.

Engineering leadership puts together a sound plan. First the objective to “Increase Company Margins” is decomposed into a collection of eng-level goals like “Reduce Tier 2 Support Hours”. Each of these eng-level goals decompose into division-level goals like “Reduce Customer Onboarding Tier 2 Support Escalations”, which decompose into team-level goals like “Reduce Customer Onboarding Exceptions”.

At the surface it may seem like the path forward is clear. Each engineering team just needs to achieve their individual goals, and the solutions will roll up into the org level goals. But the work of engineering leadership has just begun.

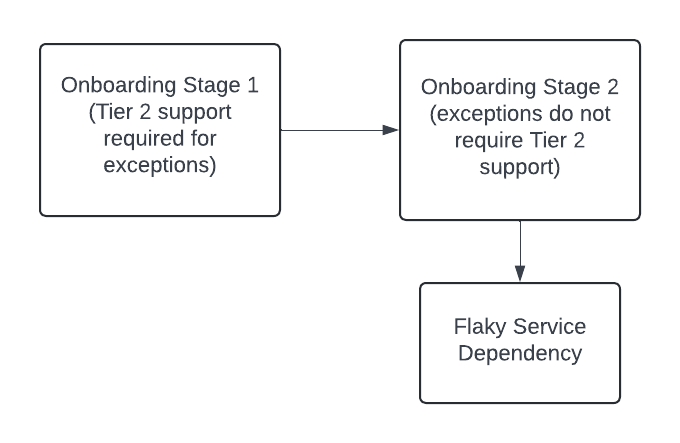

The engineer tasked with reducing customer onboarding exceptions is unlikely to understand the relationship of this workstream with company margins - they may or may not even know what Tier 2 support is. The great game of corporate telephone can easily send them down the wrong road. For example, suppose the engineer reviews recent customer onboarding exceptions, identifies a flaky service dependency as a common root cause, and then writes a design to remove the dependency. This will likely read as a solid plan to someone reviewing the design at a surface level.

But perhaps the specific exceptions triggered by this flaky service dependency do not require Tier 2 support to resolve! Then fixing these exceptions will not remove Tier 2 support, and the engineer’s plan will not help the key business goal.

Executing this plan - which might take multiple months to implement, test and deploy - means needlessly ballooning the budget and extending the timeline of a critical business initiative. Although each leader in the chain decomposed their problem nicely, the end result was failure. How can we prevent this?

The key miss is that the success criteria of “Reduce Customer Onboarding Exceptions” was fundamentally underspecified. The leader who derived this may not have known that only certain customer onboarding exceptions trigger Tier 2 support cases - this is the kind of critical detail that may be invisible to anyone who does not look at log data every week.

To solve this we need to establish a feedback loop between high level objectives, low level specifications, and technical details. This requires an extremely high degree of accountability from a small number of key decision makers - sometimes engineering managers, sometimes tech leads - who own high level objectives and feel personal responsibility for every technical decision that their team makes to achieve them.

This is the cornerstone of effective technical execution. The difference between a seemingly well-scoped project landing on time or an order of magnitude over budget can depend on whether engineering leaders with the right business and technical context have taken the time to deeply inspect critical plans, decisions, and designs.

So what exactly do these leaders need to do?

The first step is to define an initial set of success criteria. These should be:

- Comprehensive - It should not be possible to achieve these goals and still fail

- Minimal - The success criteria should focus on what needs to be achieved, not the details of how it will be achieved

- Written - There needs to be a single source of truth

- Falsifiable - The success criteria must be concrete and ideally measurable

It’s often helpful to write non-goals alongside success criteria. For example, a non-goal for the “Reduce Customer Onboarding Exceptions” workstream might be “Reduce Customer Onboarding Exceptions That Don’t Require Tier 2 Support”.

Next, the leader needs to inspect the critical decisions, designs, and plans to achieve these success criteria. This can’t be an exercise in micromanagement. Leaders have the responsibility to harness, not stifle, the unique context understood by the engineer with their hands on the keyboard. Success criteria should be somewhat prescriptive and tops down, but solutions must be bottoms up.

When executed correctly this inspection can unveil cracks and inconsistencies in the initial set of success criteria. A critical detail - like the fact that only certain customer onboarding exceptions trigger Tier 2 support cases - may only reveal itself after hours of poring over logs. At its best technical inspection is an iterative process of setting success criteria, inspecting solutions, and increasing the specificity of the success criteria.

The key ingredients of effective inspection are accountability and trust. The leader must feel personally responsible for their team’s decisions, but not be a zealot. Trust should flow in two directions - leaders must trust that their engineers will make the right decisions with the right context, and engineers must trust that their leaders will embrace a solution that is unfamiliar to them but correct. This leads to faster execution and a healthier organization.