Generative large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT are like wild beasts. They are powerful but difficult to tame.

One formidable challenge lies in the cost and latency associated with these models. Compared to traditional software solutions, LLMs can operate at a slower pace, incurring higher costs along the way. Instead of near-instantaneous responses measured in milliseconds, LLMs may require seconds to generate a reply. Moreover, their behavior can be unpredictable, as minor alterations to inputs can yield vastly different outcomes. The structure of their output is not guaranteed, necessitating meticulous error handling mechanisms.

Balancing the raw power of LLMs with their idiosyncrasies is crucial when designing software that harnesses their potential. We must carefully consider how we input data, frame our prompts, and interpret their responses. Each decision demands a deep understanding of the LLM’s capabilities and the specific requirements of the software at hand.

Within this post, we will delve into various LLM design patterns, exploring how to channel their untamed brilliance and select the most suitable approach for your needs.

What are Tools?

The most exciting kinds of AI software interpret LLM text outputs to trigger downstream effects.

One example, Tools enable the creation of autonomous AI agents. This consists of four parts:

- A function that does something the LLM cannot do itself: browse the web, search a database, run code, call a public API, use a calculator, etc

- A parser that converts the raw LLM string output into a specific set of inputs to this function

- A serializer that converts the function output to text that is returned to the LLM

- A text description of how to use the tool. This is included in the LLM prompt.

In the following section we explore a few design patterns for building these agents.

Designing Agents

Let’s say you want to build an LLM-powered question/answer system that supports queries like “what has the president of the United States done in the last month?”. Any LLM trained more than a month ago will not have this information stored in its weights, so we need to get this information from somewhere else: perhaps a news article or web search API. There are a number of ways we can design the interface between the LLM and this API.

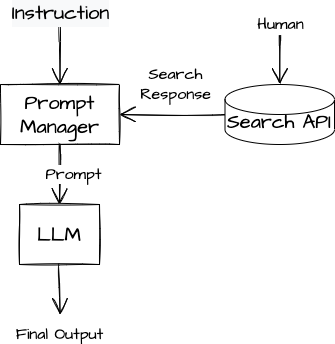

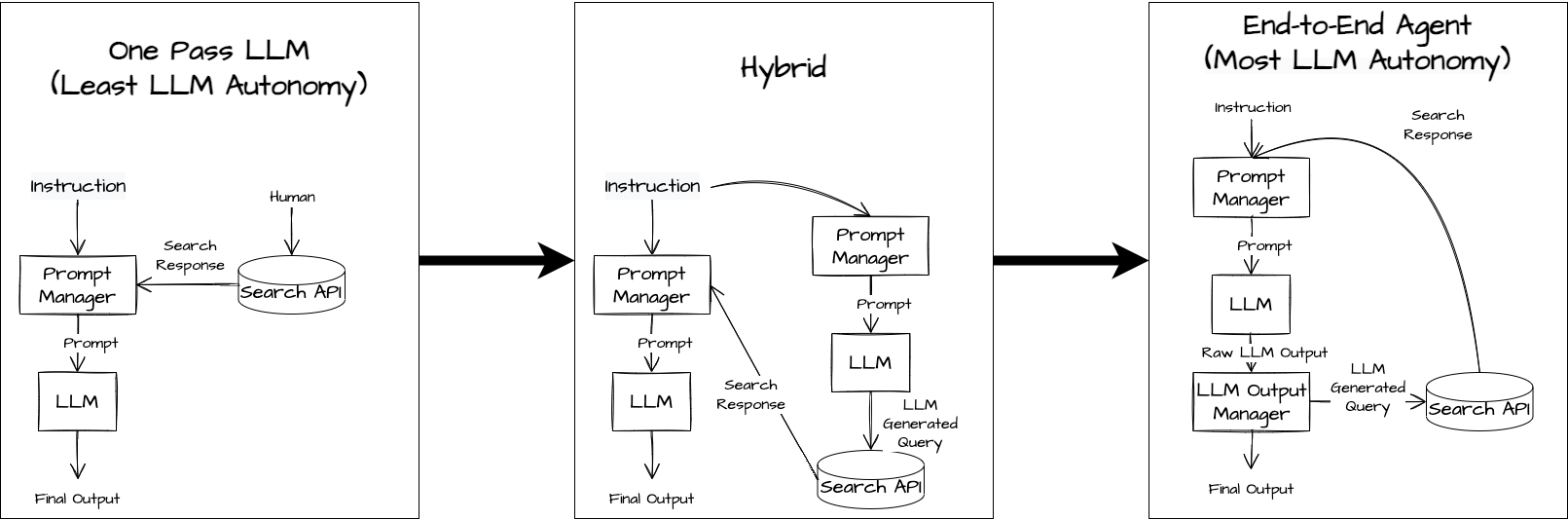

At one end of the spectrum is to do everything by hand: write the relevant queries to the search API, append the result to the original question, use the composite text as the LLM prompt, and execute the LLM in one pass.

This approach is simple, but not tremendously powerful.

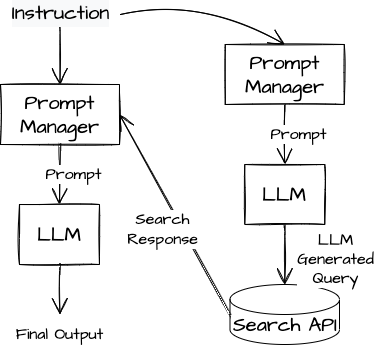

On the other end of the spectrum is an end-to-end LLM-powered agent that autonomously identifies the queries it needs from the original prompt, passes these queries to the search APIs, passes the results back to the LLM, and repeats this process until the LLM produces a final answer. This strategy requires a module to parse the LLM response into either a search query or a final result.

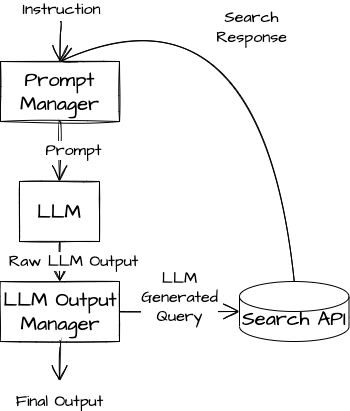

Between these extremes is a hybrid approach in which we first prompt the LLM to construct a query that will find the information it needs to complete the summary, manually run the query, and pass the query results back to an LLM in another prompt that asks it to write the summary.

This spectrum captures the degree to which the software system cedes ownership of the control flow to the LLM. Ceding more control to the LLM can allow the system to exhibit more advanced behavior.

The One Pass LLM relies entirely on human input to structure the information that the LLM uses. The hybrid approach gives the LLM control over one search query but does not enable the LLM to request additional information. The End-to-End Agent system can sequentially issue multiple search queries of increasing refinement as it sees and interprets the results of earlier search queries.

Choosing a spot on this spectrum requires a number of considerations. For example: if we expect the same query to the search API to be applicable to all questions that users may ask the Q/A system, then the One Pass LLM is probably sufficient. If we expect each query to require different underlying data then we may want to give the LLM control over the query logic.

Furthermore, an End-to-End Agent must track context across multiple executions and balance multiple input and output formats. Less powerful (cheaper) LLMs can struggle to do this effectively. In addition, these designs often involve a large number of LLM executions per query, which can be quite expensive. The One Pass and Hybrid LLMs are substantially cheaper.

Also, the more control we cede to LLMs, the larger the aperture for prompt injection. See this article for more details on prompt injection and this article to explore design patterns that minimize prompt injection risk.

Managing Context Windows

LLMs can only accept a fixed number of tokens at a time. This is known as their context window. We often want to provide our LLM with more data than could fit in its context window. We can manage this in a number of different ways.

One popular strategy is to use semantic search. We break the data into small chunks, represent each chunk with a text embedding, and store the chunks in a vector database. When we prompt our LLM we generate an embedding for the prompt, search the vector DB for the chunks with the most similar embeddings, and append these chunks to the prompt.

Another strategy is to design a search API for the data and apply the End-to-End Agent strategy from the previous section. This approach cedes a bit more control to the LLM, but might surface more relevant data.

Dealing with Mistakes

Systems that consume LLMs often expect the output to be formatted in a certain way, such as JSON. However, LLMs provide no guarantees on the format of the text they output. In most cases adding a line like return your output in the following JSON format: ... to the prompt and praying is an LLM engineer’s best option. This approach is obviously not foolproof, so any system that consumes LLM output must be prepared for unexpected responses.

LLMs may produce incorrectly formatted outputs in a number of ways. The most common failure is to simply miss the formatting specification: for example, returning a value directly without wrapping it as a JSON.

User: Who is a better rapper, Gandalf or Dumbledore? Return your result in the JSON format {"result": <result>}

Agent: I don't know who is the better rapper

As another example of the same failure case:

User: What is 13+22? Return your result in the JSON format {"result": <result>}

Agent: 35

Another failure is to include the data in the correct format as part of the response, but also return other text (such as an explanation) outside of the correctly formatted data.

User: What is 13+22? Return your result in the JSON format {"result": <result>}

Agent: {"result": 35} 13+22 is 35 because 1+2=3 and 3+2=5

There are three main ways to handle these failures:

- Fail Gracefully: This approach is a good default, especially when there are reasonable things that the system can do even when the LLM response is missing.

- Attempt to Salvage the Result: In this approach, we try to convert the LLM response to the correct format. This can work well in cases where the LLM appends unnecessary data to an otherwise correct response. However, this can be very error prone.

- Pass the Error to the LLM: In this approach, we return the error to the LLM directly and ask it to regenerate its response. This is the most autonomous result, but it can lead to chains where an LLM fails in the same way many times in a row, burning money in the process.

Less powerful LLMs are more likely to produce incorrectly formatted responses, and therefore require more hands-on error handling. Overly large and complex prompts can also confuse even the most powerful LLMs into generating badly formatted responses.

Conclusion

Designing software involves striking a delicate balance between various attributes and considerations. Engineers weigh factors such as simplicity, speed, cost, and effectiveness as they make design choices. Each design represents a different point on the tradeoff spectrum.

These design patterns are just a small glimpse into the strategies that engineers will explore as LLMs permeate throughout the software ecosystem. As new use cases for LLMs arise, engineers will design and develop new patterns to use them.