ML models are collaboration bottlenecks.

Suppose your team owns a binary classification model, and you have decided that increasing this model’s recall without reducing precision is very important for the business. You’ve put 5-10 engineers on the job.

The Problem

What should these engineers do? There are many ways to improve a model, including adding new features, modifying the model architecture, changing the training procedure, etc. However, parallelizing this work is challenging. If one engineer works on adding a new feature and another works on modifying the training procedure, there is often no simple way to combine their work.

ML development often includes a notebook stage in which most experimental code that is written is thrown out. This encourages engineers to work in independent branches for long periods of time, which makes collaboration extremely difficult.

To make things worse, different atoms of ML work are rarely additive. For example, if an engineer would like to experiment with a new feature they may limit their training data to only samples where this new feature is available. Other engineers working on new architectures or training paradigms do not share this restriction, which can create friction when combining work.

Finally, taking any engineer’s work into production requires an online model deployment, but only one model can go through this process at a time. This leads to tournament style experimention, where engineers compete to get their version of the model into production before another engineer shifts the goalposts. This is the opposite of incremental development and is an extremely inefficient use of ML engineering resources.

Avoiding the Problem

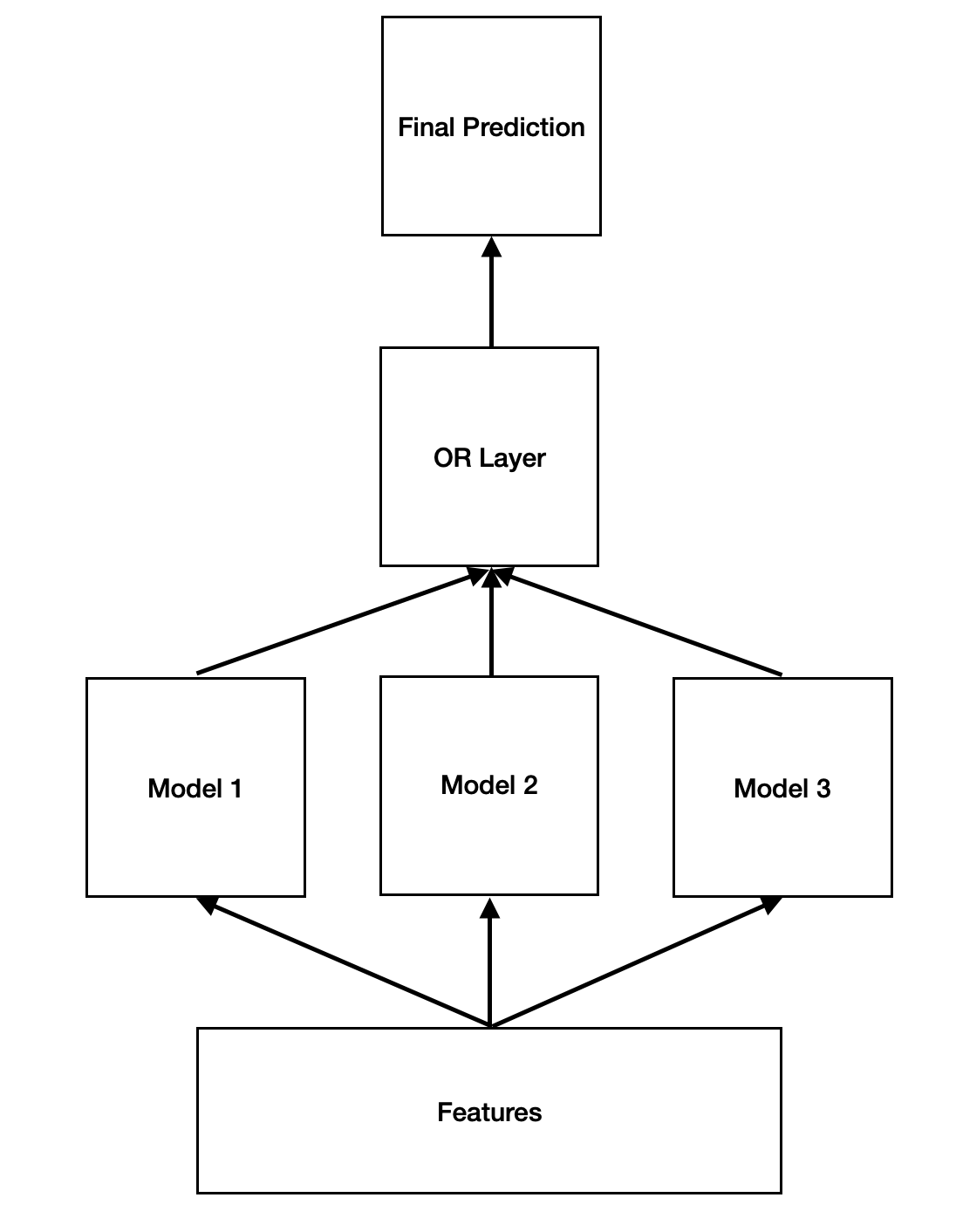

We can avoid the problem entirely with a simple trick: run a suite of models in parallel. Here’s how this could work in our binary classification setting.

First, run each model in the suite to generate a True or False judgement. Define the final judgement to be True if any model predicts True. The unique precision of any model in the suite is the precision of the set of samples where that model returns True and all others return False.

It may be tempting to replace this OR with a different kind of layer, such as a lightweight ensemble, but this will reintroduce the bottleneck in a new form. The power of the OR is its simplicity and interpretablity, which provides a simple blueprint for iterative improvement:

- Increase Recall Add a new model whose unique precision is no less than the overall precision.

- Increase Precision Take the model with the lowest unique precision and either remove this model or improve its precision.

Engineers can apply this blueprint at the same time to different models, making incremental improvements collaboratively. Intuitively, this system forms an uber-model that is optimized for interpretability and incremental editability.

Deploying multiple models may not be an option in a heavily latency constrained system. Luckily, there are ways around this. For example, we can deploy the heaviest parts of models (e.g. image or text transformers) to a preprocessing layer that provides embeddings to all of the classification models.

Conclusion

Increasing headcount is never a surefire way to scale engineering delivery, and this is especially true in the ML world. The experimental nature of ML work adds serious complexity to day-to-day collaboration. There are some ways to structure teams to minimize these problems, such as pair programming, but these are challenging at best and nearly impossible in a remote environment.

An alternative solution is to design systems that facilitate collaborative and incremental development. Federated technical designs that allow engineers to work independently can reduce communication overhead and increase team efficiency.