Clustering algorithms allow us to group points in a dataset together based on some notion of similarity between them. Formally, we can consider a clustering algorithm as mapping a metric space \((X, d_X)\) (representing data) to a partitioning of \(X\).

In most applications of clustering the points in the metric space \((X, d_X)\) are grouped together based solely on the distances between the points and the rules embedded within the clustering algorithm itself. This is an unsupervised clustering strategy, since no labels or supervision influence the algorithm output. For example, agglomerative clustering algorithms like HDBSCAN and single linkage partition points in \(X\) based on graphs formed from the points (vertices) and distances (edges) in \((X, d_X)\).

However, there are some circumstances under which we have a few ground truth examples of pre-clustered training datasets and want to learn an algorithm that can cluster new data in as similar of a way as possible. That is, given a collection of tuples \(\mathbf{S} = \{(X_1, d_{X_1}, P_{X_1}), (X_2, d_{X_2}, P_{X_2}), \cdots, (X_n, d_{X_n}, P_{X_n})\}\) where \(P_X\) is a partition of \(X\) we would like to learn a function \(f: (X, d_X) \rightarrow (X, P_X)\) such that for each \((X_i, d_{X_i}, P_{X_i}) \in \mathbf{S}\) we have \(f(X_i, d_{X_i}) \sim (X_i, P_{X_i})\).

In this blog post we will demonstrate how we can utilize the Kan Extension, a fundamental tool of Category Theory, to solve this problem.

Functorial Perspective on Clustering

In order to invoke the Kan Extension for clustering extrapolation we will use a functorial perspective on clustering. We begin with the following definitions. For more information see Section 4 of Category Theory in Machine Learning:

- In the category \(\mathbf{Met}\) objects are metric spaces \((X, d_X)\) and morphisms are non-expansive maps \(f: (X, d_X) \rightarrow (Y, d_Y)\) such that \(d_Y(f(x_1), f(x_2)) \leq d_X(x_1, x_2)\).

- In the category \(\mathbf{Part}\) objects are tuples \((X, P_X)\) where \(P_X\) is a partitioning of \(X\) and morphisms are functions \(f: (X, P_X) \rightarrow (Y, P_Y)\) such that if \(\exists S_X \in P_X, x_1, x_2 \in S_X\) then \(\exists S_Y \in P_Y, f(x_1), f(x_2) \in S_Y\).

- Given a subcategory \(\mathbf{D}\) of \(\mathbf{Met}\), a clustering functor is a functor \(F: \mathbf{D} \rightarrow \mathbf{Part}\) that is the identity on the underlying set (i.e. \(F\) commutes with the forgetful functors that map \((X, d_X)\) and \((X, P_X)\) to \(X\)).

We can now frame our goal as follows. Given a category \(\mathbf{D}\) of metric spaces, a discrete (no non-identity morphisms) subcategory \(\mathbf{T} \subseteq \mathbf{D}\) (the training set) and a clustering functor \(K: \mathbf{T} \rightarrow \mathbf{Part}\), find a \(\)clustering functor \(F: \mathbf{D} \rightarrow \mathbf{Part}\) that agrees with \(K\) on \(\mathbf{T}\) as best as possible.

Kan Extensions for Extrapolation

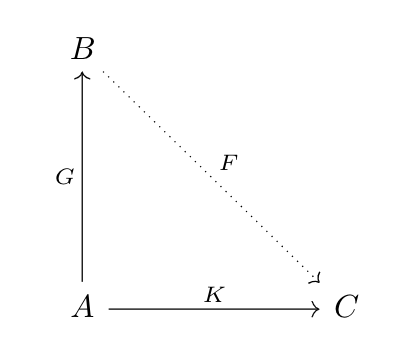

Suppose we have three categories \(A, B, C\) and two functors \(G: A \rightarrow B, K: A \rightarrow C\). A Kan Extension of \(K\) along \(G\) is a functor \(F: B \rightarrow C\) that we build from these components in a universal way.

Formally, there are two ways that we can construct a Kan Extension:

- The Right Kan Extension of \(K\) along \(G\) is the universal pair of the functor \(RanK: B \rightarrow C\) and natural transformation \(\mu: (RanK \circ G) \rightarrow K\) such that for any pair of a functor \(M: B \rightarrow C\) and natural transformation \(\lambda: (M \circ G) \rightarrow K\) there exists a natural transformation \(\sigma: M \rightarrow RanK\) such that \(\lambda = \mu \circ \sigma_G\) (where \(\sigma_G(a) = \sigma(G a)\)).

- The Left Kan Extension of \(K\) along \(G\) is the universal pair of the functor \(LanK: B \rightarrow C\) and natural transformation \(\mu: K \rightarrow (LanK \circ G)\) such that for any pair of a functor \(M: B \rightarrow C\) and natural transformation \(\lambda: K \rightarrow (M \circ G)\) there exists a natural transformation \(\sigma: LanK \rightarrow M\) such that \(\lambda = \sigma_G \circ \mu\) (where \(\sigma_G(a) = \sigma(G a)\)).

Intuitively, if we treat \(G\) as an inclusion of \(A\) into \(B\) then the Kan Extension of \(K\) along \(G\) acts as an extrapolation of \(K\) from \(A\) to all of \(B\). That is, both the left and right Kan extensions will be equal (up to natural transformation) to \(K\) on the image of \(G\) in \(B\), and on the rest of \(B\) the left/right Kan extensions will respectively be the smallest/largest such extrapolations.

For example, suppose we want to use a Kan extension to interpolate a monotonic function \(K: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) to a function \(F_K: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\). In this case \(A=\mathbb{Z}, B=C=\mathbb{R}\) (objects are numbers and morphisms are \(\leq\)) and \(G: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is the inclusion map. We have that \(LanK: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is simply \(K \circ floor\) and \(RanK: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is simply \(K \circ ceil\), where \(floor, ceil\) are the rounding down and rounding up functions respectively.

We can use Kan extensions to solve the clustering problem posted above. Suppose the discrete category \(A=\mathbf{T}\) is our training set, \(B=\mathbf{D}\) is our category of metric spaces, and \(C=\mathbf{Part}\). Then we have:

- \(RanK: \mathbf{D} \rightarrow \mathbf{Part}\) maps the metric space \((X, d_X)\) to the transitive closure of the relation \(R\) where for \(x_1, x_2 \in X\) we have \(x_1 R x_2\) if for any metric space \((X^{'}, d_{X^{'}}) \in \mathbf{T}\) and \(f: (X, d_X) \rightarrow (X^{'}, d_{X^{'}})\) in \(\mathbf{D}\) it is the case that \(f(x_1), f(x_2)\) are in the same partition in \(K(X^{'}, d_{X^{'}})\). The components of the natural transformation \(\mu: (RanK \circ G) \rightarrow K\) are identity functions, which are non-expansive by the definition of \(R\).

- \(LanK: \mathbf{D} \rightarrow \mathbf{Part}\) maps the metric space \((X, d_X)\) to the transitive closure of the relation \(R\) where for any metric space \((X^{'}, d_{X^{'}}) \in \mathbf{T}\) and \(f: (X^{'}, d_{X^{'}}) \rightarrow (X, d_{X})\) in \(\mathbf{D}\), if the points \(x_1^{'}, x_2^{'} \in X^{'}\) are in the same partition in \(K(X^{'}, d_{X^{'}})\) we have \(f(x_1^{'}) R f(x_2^{'})\). The components of the natural transformation \(\mu: K \rightarrow (LanK \circ G)\) are identity functions, which are non-expansive by the definition of \(R\).

Intuitively, \(RanK(X, d_X)\) is the coarsest (fewest partitions) clustering and \(LanK(X, d_X)\) is the finest (most partitions) clustering such that \(LanK=RanK=K\) on metric spaces in \(\mathbf{T}\) and functoriality over \(\mathbf{D}\) is satisfied.

Extrapolation Algorithm

We can treat the left and right Kan extensions as algorithms that map training datasets to clustering functors. There are two sources of structure that they can take advantage of: the functor \(K\) and the category \(\mathbf{D}\). Intuitively, the more restrictive that \(\mathbf{D}\) is (e.g. the more morphisms in \(\mathbf{D}\)) or the larger that \(\mathbf{T}\) is (and therefore the more information that is stored in \(K\)) the more similar that these algorithms will be to each other.

Example 1

Suppose

\[\mathbf{D}=\{(\{x_1,x_2\}, d), (\{x_1,x_3\}, d), (\{x_2,x_3\}, d), (\{x_1,x_2,x_3\}, d)\} \qquad \mathbf{T}=\{(\{x_1,x_2\}, d), (\{x_1,x_3\}, d), (\{x_2,x_3\}, d)\}\]are discrete subcategories (no non-identity morphisms) of \(\mathbf{Met}\) and \(K: \mathbf{T} \rightarrow \mathbf{Part}\) is a clustering functor defined as:

\[K(\{x_1,x_2\}, d) = \{\{x_1, x_2\}\} \qquad K(\{x_1,x_3\}, d) = \{\{x_1\},\{x_3\}\} \qquad K(\{x_2,x_3\}, d)) = \{\{x_2\},\{x_3\}\}\]Then on metric spaces in \(\mathbf{T}\) we have \(K=RanK=LanK\) and on \((\{x_1,x_2,x_3\}, d)\) we have:

- \(RanK(\{x_1,x_2,x_3\}, d) = \{\{x_1,x_2,x_3\}\}\) since there are no metric spaces in \(\mathbf{T}\) with more than \(2\) points.

- \(LanK(\{x_1,x_2,x_3\}, d) = \{\{x_1,x_2\}, \{x_3\}\}\) since the only points that need to be put together are \(x_1, x_2\).

Example 2

Suppose

\[\mathbf{D}=\{(\{x_1,x_2,x_3\}, d), (\{x_1,x_2\}, d), (\{x_2,x_3\}, d)\} \qquad \mathbf{T}=\{(\{x_1,x_2,x_3\}, d), (\{x_1,x_2\}, d)\}\]are discrete subcategories of \(\mathbf{Met}\) and \(K: \mathbf{T} \rightarrow \mathbf{Part}\) is a clustering functor defined as:

\[K(\{x_1,x_2,x_3\}, d) = \{\{x_1, x_2\}, \{x_3\}\} \qquad K(\{x_1,x_2\}, d) = \{\{x_1, x_2\}\}\]Then on metric spaces in \(\mathbf{T}\) we have \(K=RanK=LanK\) and on \((\{x_2,x_3\}, d)\) we have:

- \(RanK(\{x_2,x_3\}, d) = \{\{x_2\}, \{x_3\}\}\) since \(x_2,x_3\) are not together in \(K(\{x_1,x_2,x_3\}, d)\).

- \(LanK(\{x_2,x_3\}, d) = \{\{x_2\}, \{x_3\}\}\) since there is no metric space in \(\mathbf{T}\) that contains \(x_2, x_3\) and has fewer than \(3\) points.

Example 3

Let’s start with some background:

Given a metric space \((X, d_X)\), we can think of its \(\delta\)-Vietoris Rips complex as a graph in which the vertices are \(X\) and there exists an edge between \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) when \(d_X(x_1, x_2) \leq \delta\). The \(\delta\)-single linkage clustering functor maps a metric space \((X, d_X)\) to the connected components of its \(\delta\)-Vietoris Rips complex. The \((\delta, k)\)-robust single linkage functor maps a metric space \((X, d_X)\) to the connected components of the \(\delta\)-Vietoris-Rips complex of the metric space \((X, d_{X}^{k})\) where \(d_{X}^{k}(x_1, x_2) = max(d_X(x_1, x_2), \mu_{X_k}(x_1), \mu_{X_k}(x_2))\) and \(\mu_{X_k}(x_1)\) is the distance from \(x_1\) to its \(k\)th nearest neighbor. Intuitively, robust single linkage reduces the impact of dataset noise by increasing distances in sparse regions of the space.

Note that robust single linkage is not a clustering functor on \(\mathbf{Met}\) because it includes a \(k\)-nearest neighbor computation that is sensitive to the cardinality of \(X\). However, it is a clustering functor on the restriction of \(\mathbf{Met}\) to its subcategory in which morphisms are restricted to injections (Carlsson et. al.).

Now suppose \(\mathbf{D}=\mathbf{Met}\), \(\mathbf{T}\) is some discrete subcategory of \(\mathbf{D}\), and \(K: \mathbf{T} \rightarrow \mathbf{Part}\) is the \((\delta, k)\)-robust single linkage algorithm. Since robust single linkage is not functorial over all of \(\mathbf{Met}\), it may not be the case that \(K=RanK=LanK\) on metric spaces in \(\mathbf{T}\).

However, by the universal property of the Kan extension it must be that \(RanK, LanK\) commute with the forgetful functor (i.e. are clustering functors), since if they do not then they will respectively refine/be refined by a functor that does. Therefore, by Carlsson et. al. both \(RanK\) and \(LanK\) must be \(\delta\)-single linkage functors for some \(\delta_{RanK}, \delta_{LanK}\):

- \(\delta_{RanK}\) must be the largest it can be such that the output of the \(\delta\)-single linkage functor refines the output of the \((\delta, k)\)-single linkage functor, so \(\delta_{RanK}=\delta\).

- \(\delta_{LanK}\) must be the smallest it can be such that the output of the \(\delta\)-single linkage functor is always refined by the output of the \((\delta, k)\)-single linkage functor, so \(\delta_{LanK}=max(\delta, \sup \{\mu_{X_k}(x) \mid x \in X, (X, d_X) \in \mathbf{T}\})\).

Next Steps

It is clear that Kan extensions can be useful for deriving a clustering algorithm from labeled data.

For example, if different groups of human labellers have hand-categorized many sets of items based on their internal similarities (as opposed to pre-defined categories), we can use Kan extensions to pick out common underlying categories.

More concretely, suppose we have a collection of Tweets that we would like to group into categories. We can construct \(\mathbf{T}\) by repeatedly sampling 5-6 very different authors and collecting all Tweets written by those authors into metric spaces (e.g. with word2vec or transformer embedding distance). We can then define \(K\) to simply partition each set of Tweets in \(\mathbf{T}\) by author. The right and left Kan extensions would then be the coarsest/finest clustering algorithms that follow these authorship guidelines and satisfy the functoriality constraint encoded by the morphisms in \(\mathbf{D}\).

However, this procedure is not trivial to implement, since “best among all maps that are functorial over \(\mathbf{D}\)” is difficult to compute. The next step is to figure this out and test out the performance of this procedure.